Fifteen, Twenty, Twenty Five

A story about why we should cool burn injuries

Burn injuries are common worldwide and first aid recommendations always include cooling. Little is known about the effects of cooling and no one has ever quantified any benefit to cooling a burn injury in humans. We all know the soothing effect of cold water on a burn and studies have shown that patients who have received good first aid need surgery less often than those with no first aid.

It is difficult to draw any firm conclusions from these studies however, because every accident is slightly different and every wound is cooled at a different temperature for a different time. We felt that only a proper controlled investigation would tell us the true story of how much cooling helps. To recommend any intervention it's crucial we not only prove its benefit, but in quantifying its effectiveness, we can temper our advice in a proportional manner.

But where to start? What sort of burn might benefit most from first aid? What of the obvious ethical and logistical barriers to studying this in humans?

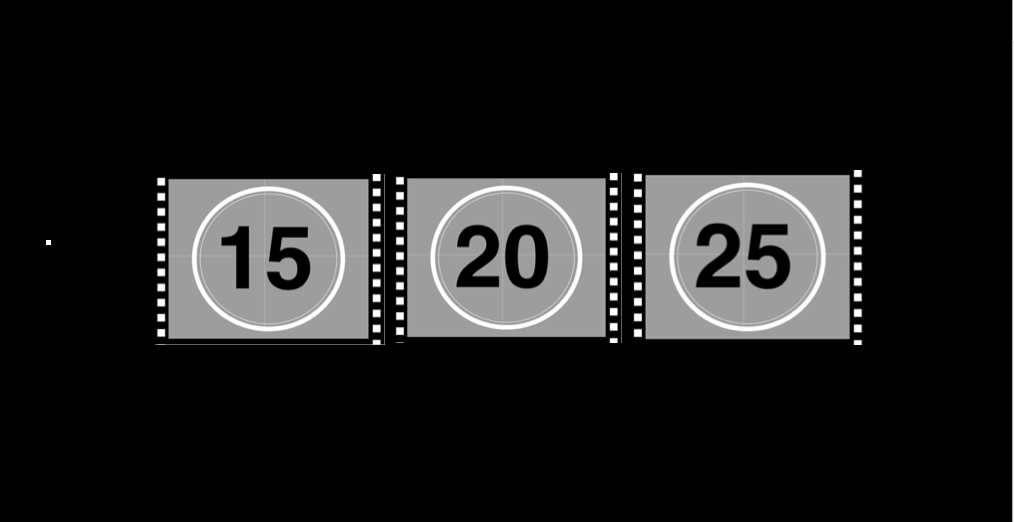

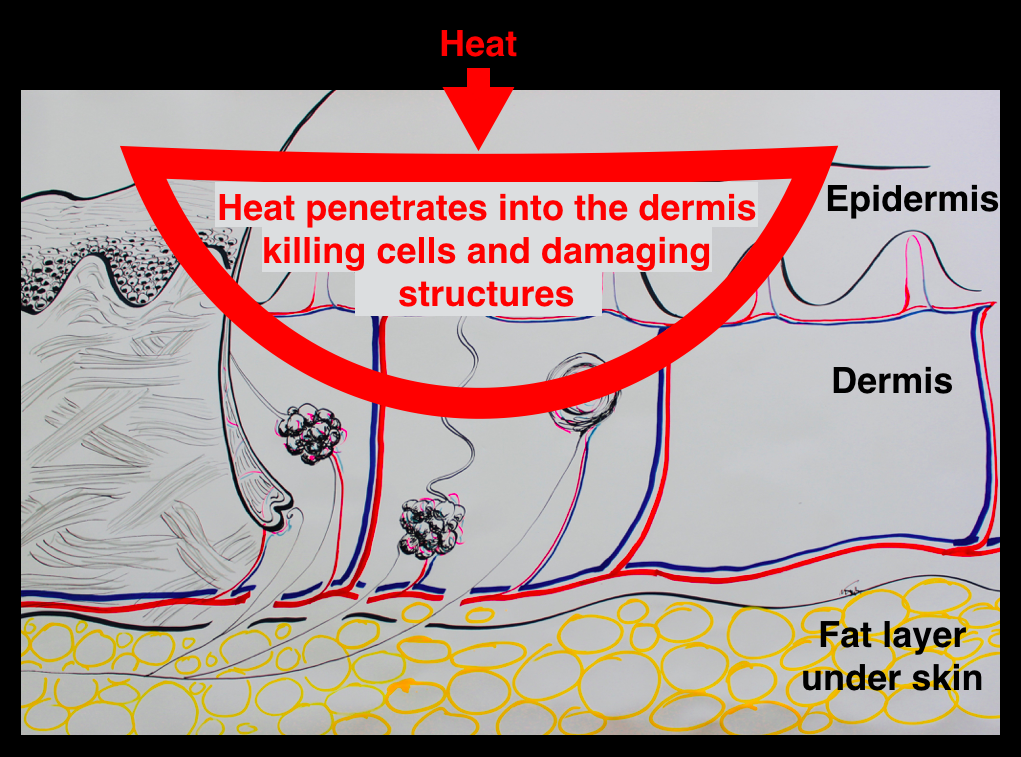

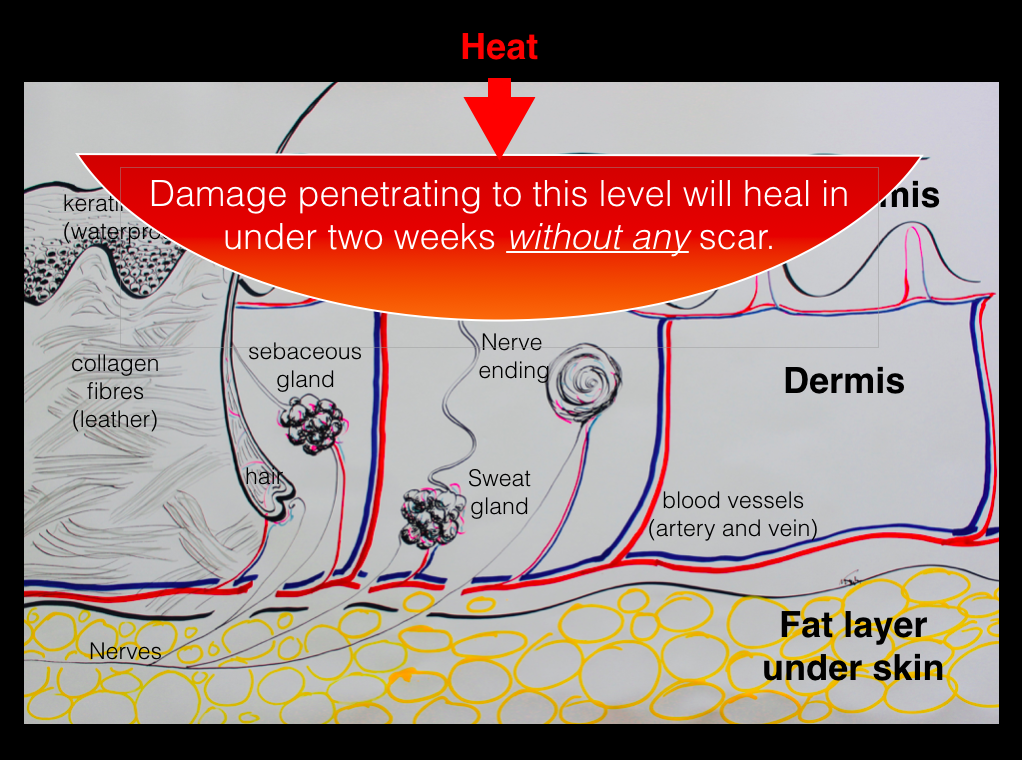

First we looked at the structure of the skin and what sort of burn we wanted to study:

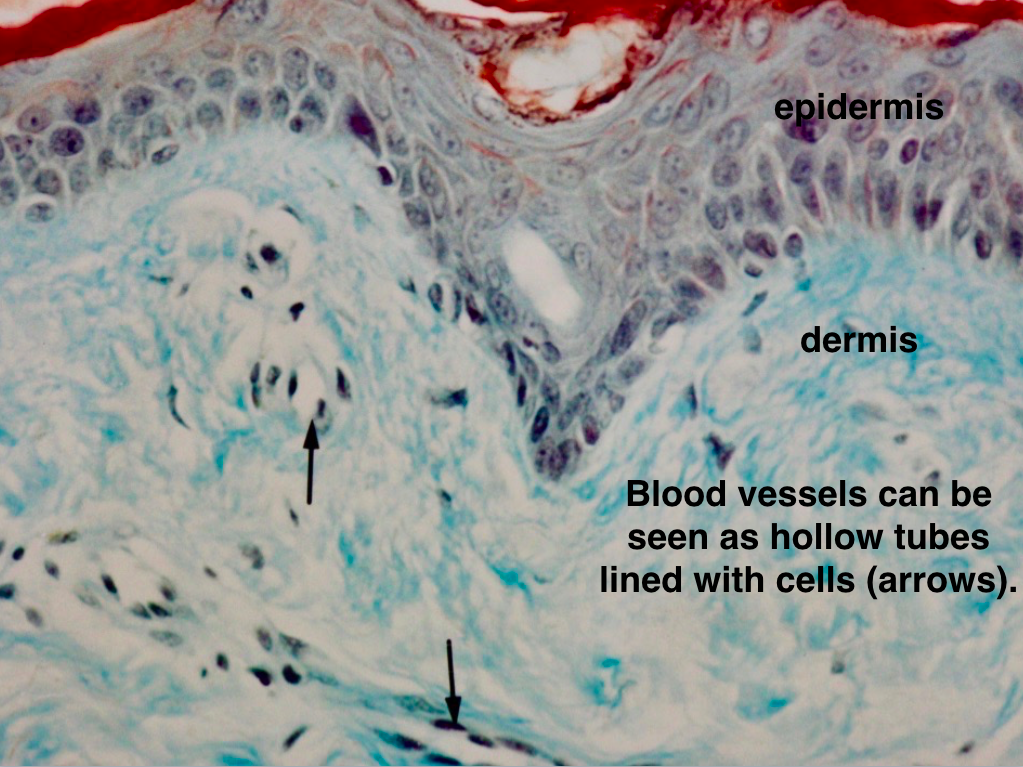

Skin is a complex structure with two main layers: the top waterproof layer called the epidermis (the layer which blisters). Underneath that, is a thick, tough layer of collagen fibres called the dermis (the protective leather-like layer). Many structures weave their way through these tough fibres such as blood vessels, nerves, hairs, sebaceous glands and sweat glands.

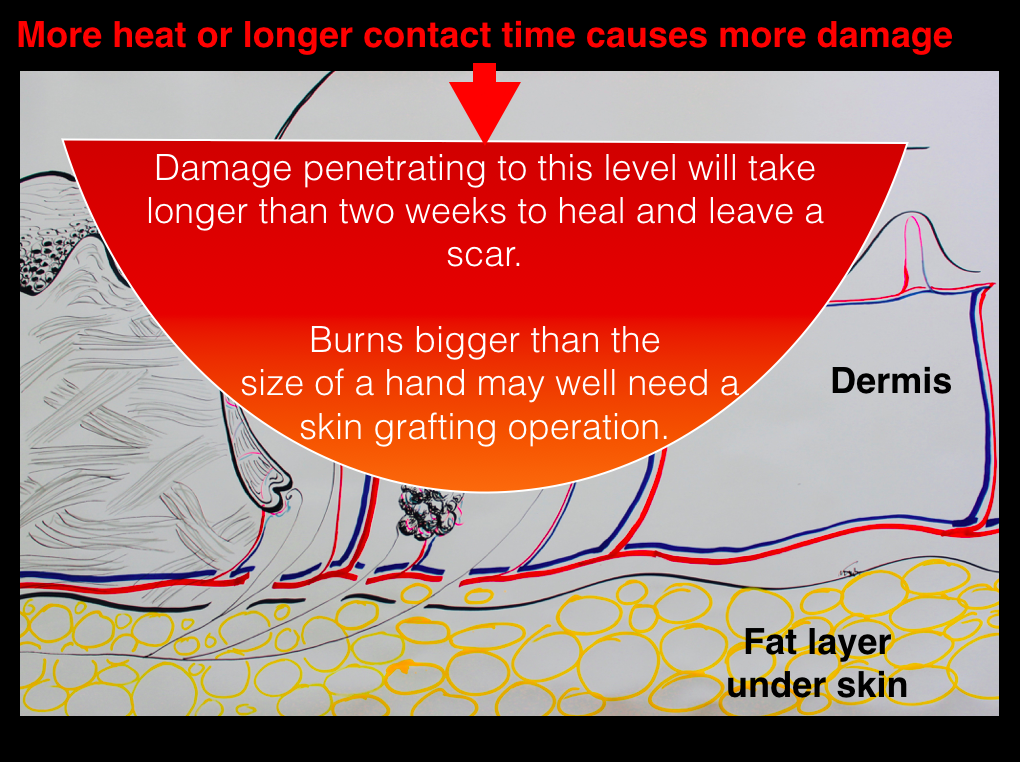

Heat destroys the cells and damages these important structures. A small amount of heat will damage the upper layers only and these burns will heal with no visible scar. More heat (either a higher temperature and/or a longer contact time) will cause more damage. Crucially, at a certain critical point scarring becomes inevitable, therefore the depth of damage caused by burns is absolutely related to outcome: Life long scarring or no visible damage at all.

The boundary between the two depths of burn described above is often very fine. Just a few seconds longer contact time or a few degrees hotter can radically alter the outcome at this critical depth of injury.

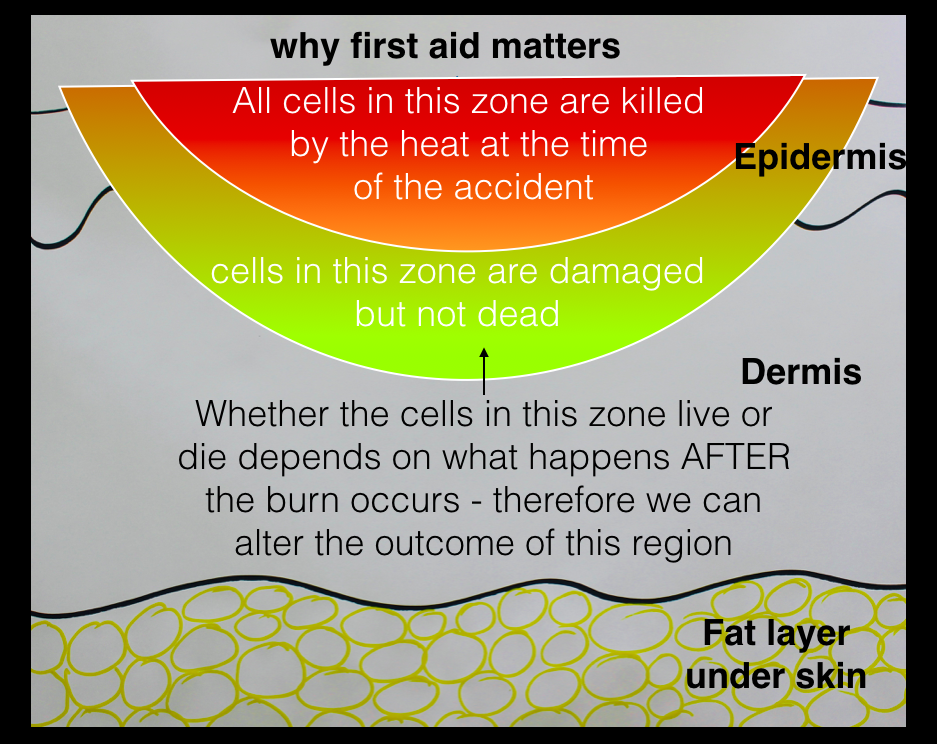

So how could first aid potentially help, or put another way: How can the amount of damage an accident causes be altered after the event?

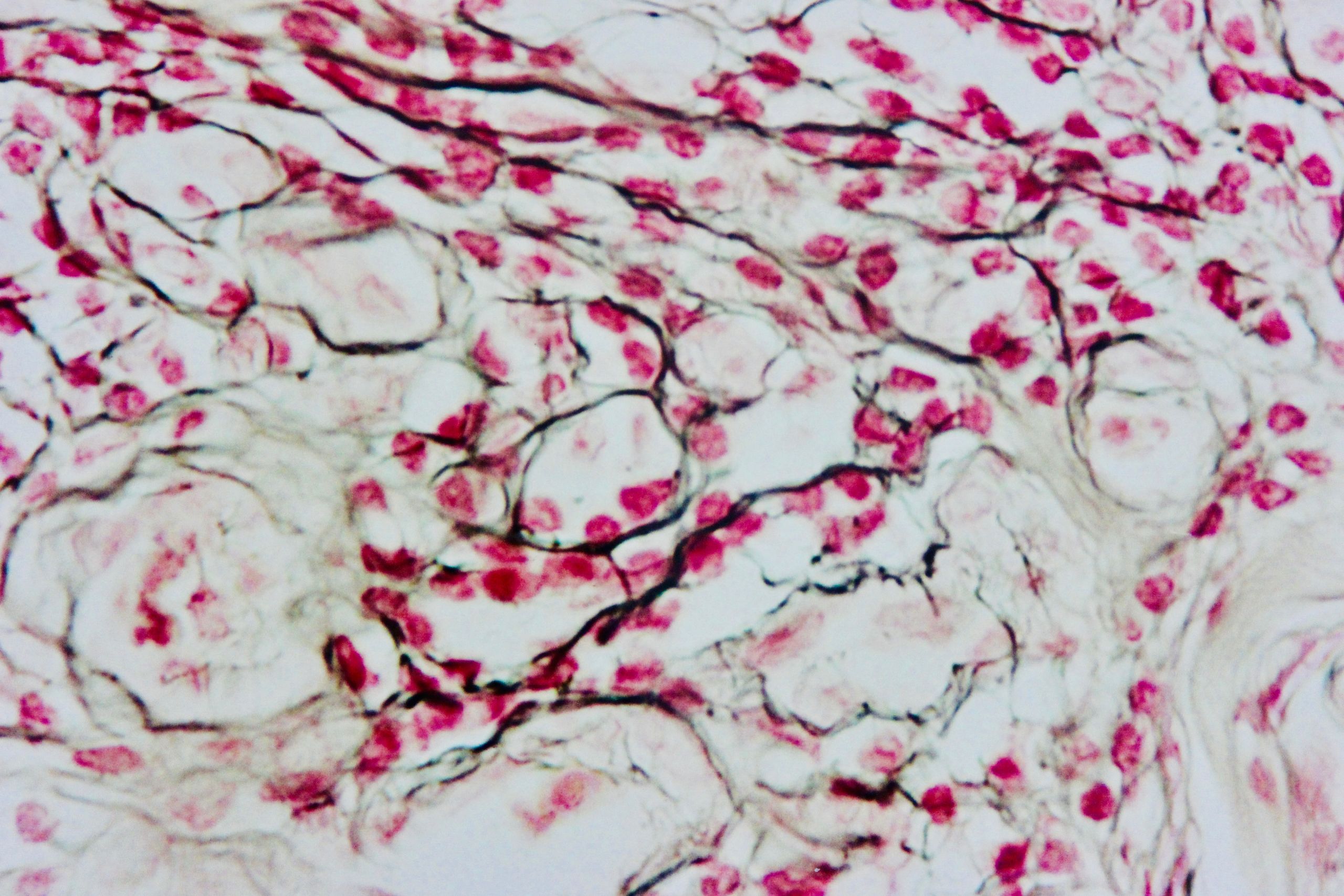

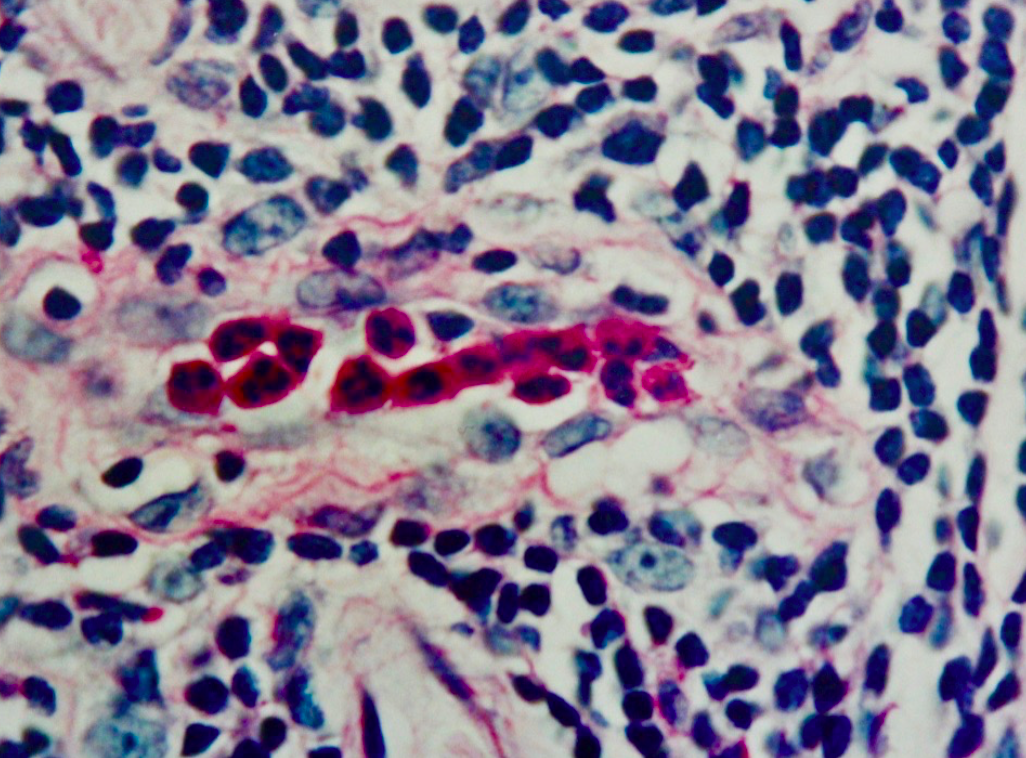

Microscope picture of a damaged area undergoing repair

This area will survive and heal with no visible scar

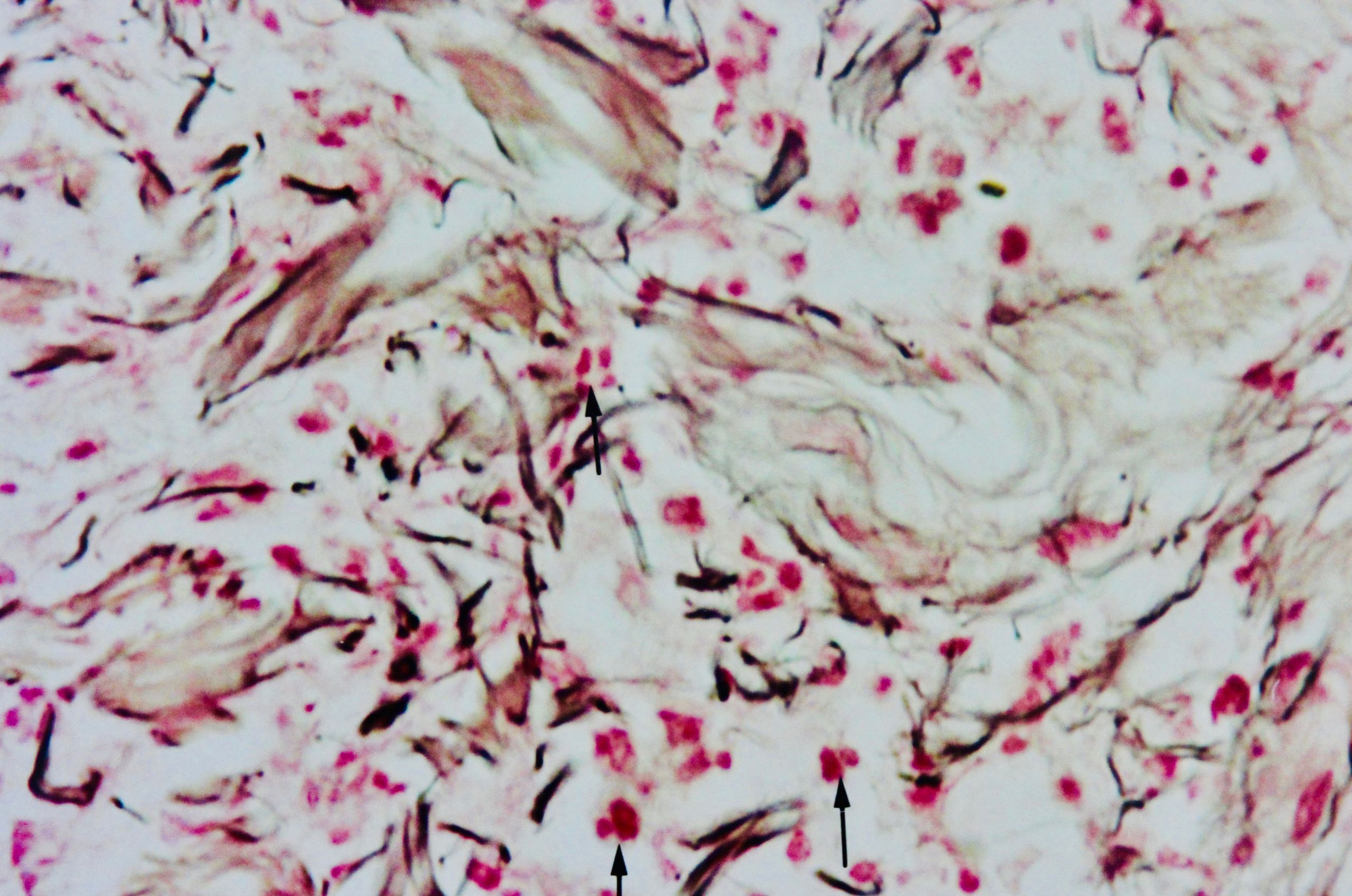

An area of irreparable damage

This area will be replaced with life long scar tissue

So we set out to study the effects of cooling. We knew it would have to be in humans to be truly relevant. We also wanted a design that would allow us to study the mechanism of benefit (if there was one) as that might allow us to identify a therapeutic pathway later, a kind of "cooling medicine"; especially useful in environments where cold water is not readily available.

We wanted to study the type of burn at that critical depth which hovers between scar and no scar. Clinically we often see this sort of injury in scalding burns from spilt hot tea and coffee. These are usually injuries caused by liquids at temperatures between 900C and 600C (190 -1400F), with contact times ranging from a couple of seconds to tens of seconds. These are the depth of burns where small changes can make a significant difference.

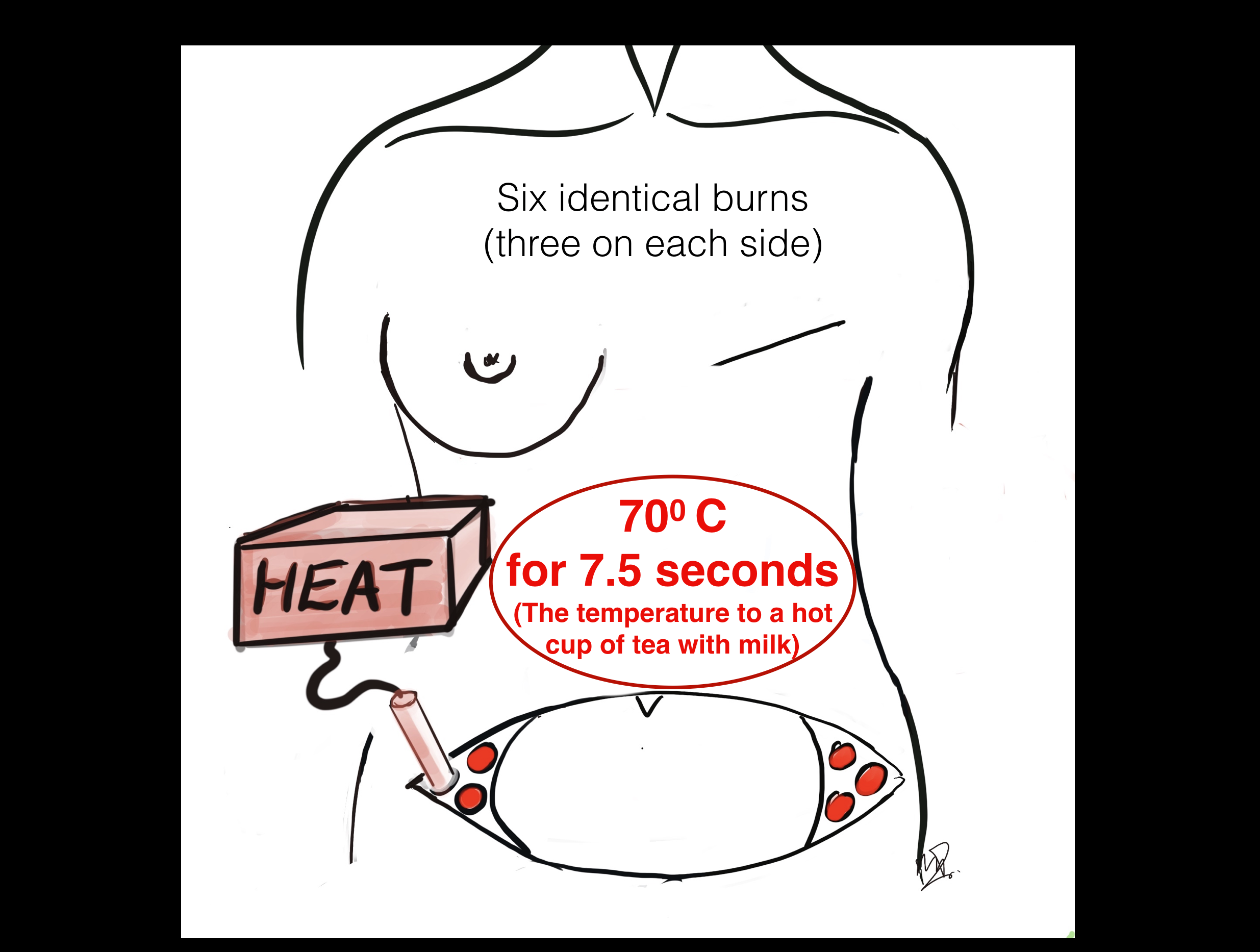

We needed therefore to create a burn with time and temperature similar to a scalding injury in human volunteers. We needed at least two burns from each volunteer: One we would cool and the other we would leave alone so that we could then examine the difference between the two. We needed multiple volunteers to ensure any effect we observed was repeatable. We needed to do this painlessly and without harming any volunteers. A difficult set of ethical and logistical barriers to overcome.

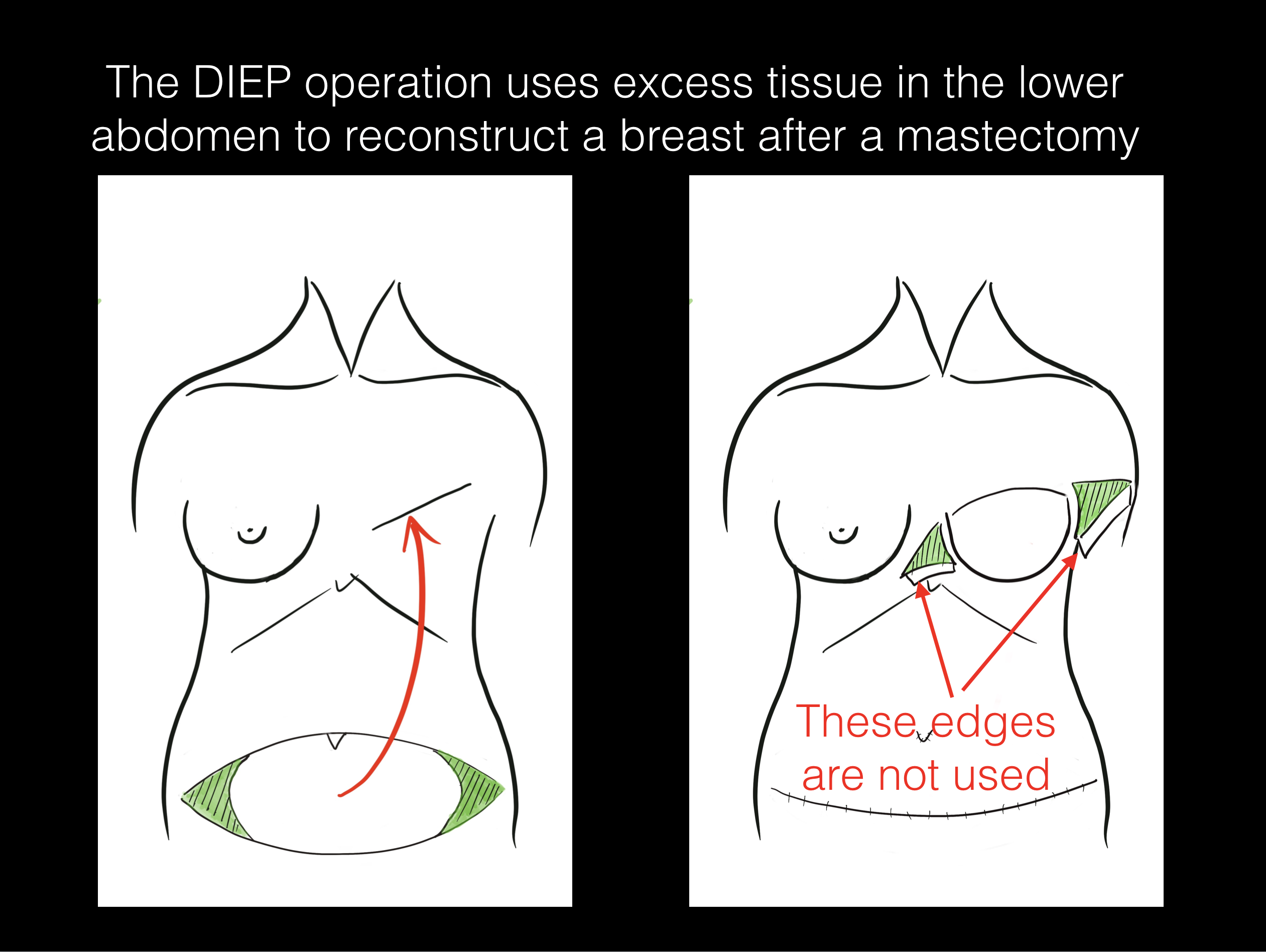

We knew that there was an operation that we commonly did where we discarded healthy skin as a normal part of the procedure; a technique used to reconstruct a breast after a mastectomy. We sought ethical permission to ask our future patients if they would consent to be involved in this study which was granted.

We asked our patients if we could create some small burns in the tissue that was to be discarded once they were asleep under anaesthesia. All the patients we asked were happy to be involved in this study and we are very grateful to them all.

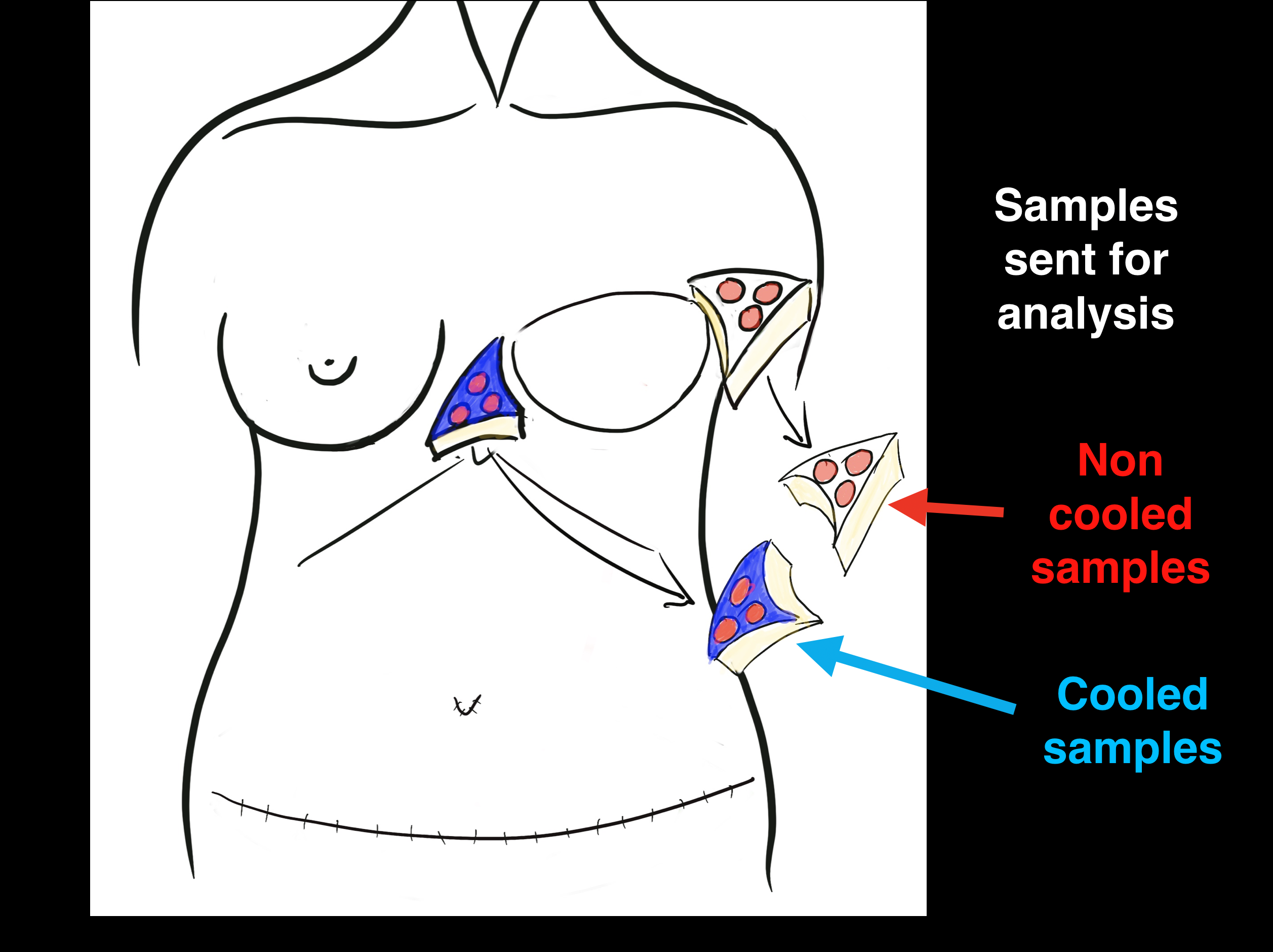

Just after the patients we anaesthetised, six small burns, one centimeter in diameter, were created at 700C (1580F) for seven and a half seconds. Three were on the right side and three on the left. This created a burn of the depth we wished to study.

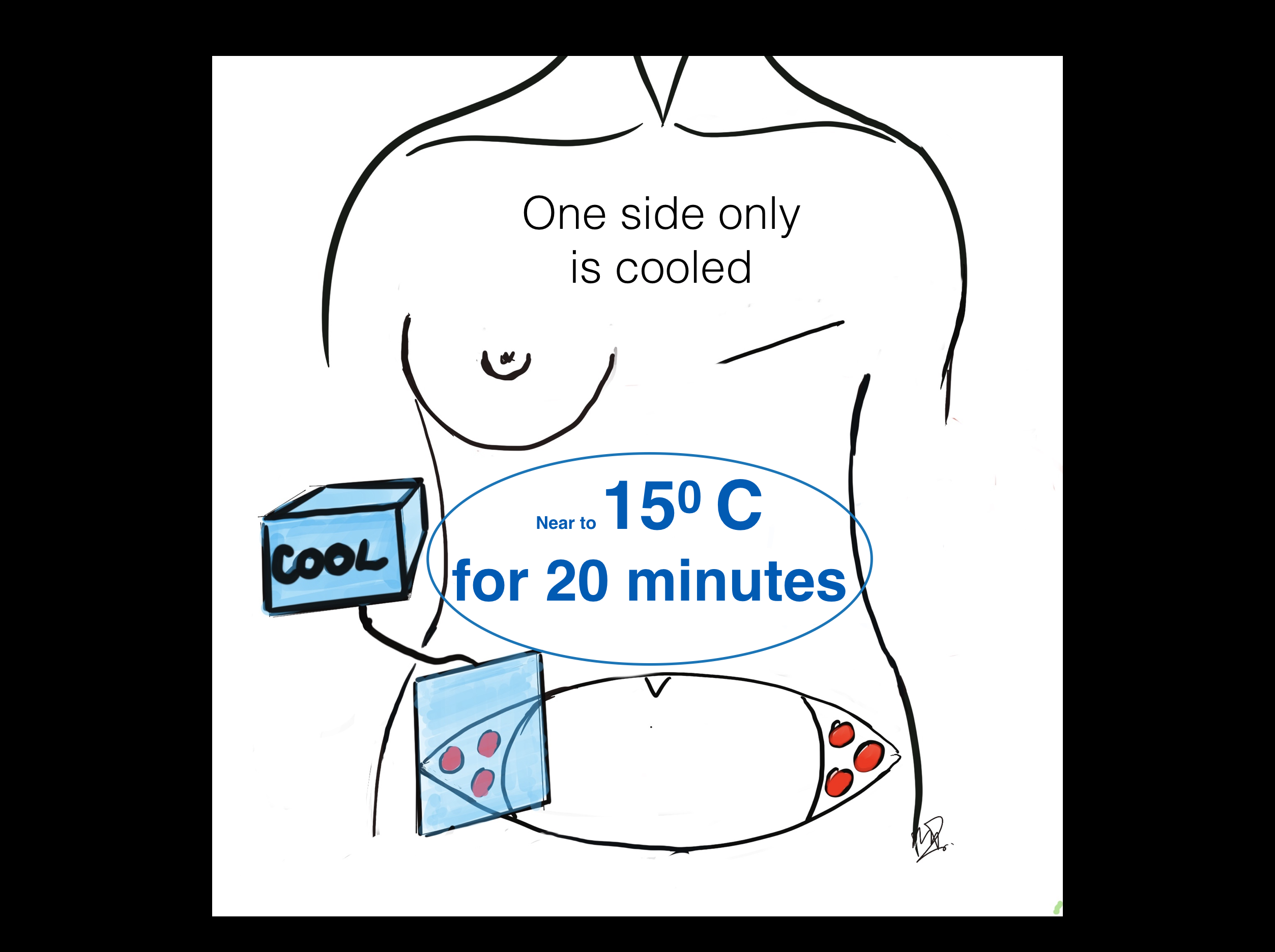

Two minutes after the burn injury, we then cooled one side at 160C (600F) for twenty minutes. During this time the patient was being prepared for the operation in the normal way and this process did not interfere with normal routine.

Three hours into the operation (it often takes about five hours), we removed the edges of skin that were due to be discarded and we sent them to the lab for analysis.

Our results

Our results

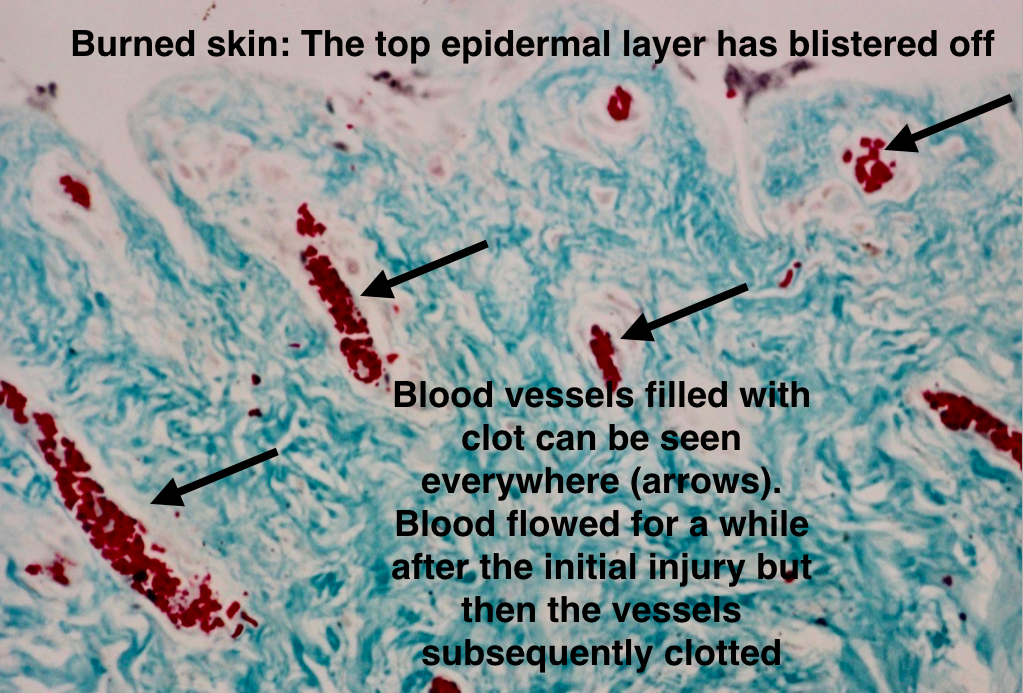

We measured the amount of damage caused by the burn by looking for damage to the blood vessels within the skin. These delicate structures are easily damaged by heat. When the cells lining the blood vessel die, the blood within it will clot and this can be easily seen under the microscope, as shown in the second picture below. Using this method we could measure how deeply the heat had penetrated into the dermis.

Normal skin showing both the epidermis and the dermis. There are no clots in the blood vessel.

Normal skin showing both the epidermis and the dermis. There are no clots in the blood vessel.

Burned skin: The epidermis has been lost in the accident and the vessels are clearly seen blocked by red blood cells (arrows). We can see how deep these blocked vessels are and thereby measure the depth of burn.

Burned skin: The epidermis has been lost in the accident and the vessels are clearly seen blocked by red blood cells (arrows). We can see how deep these blocked vessels are and thereby measure the depth of burn.

So does cooling a burn really make a difference?

answer:

YES

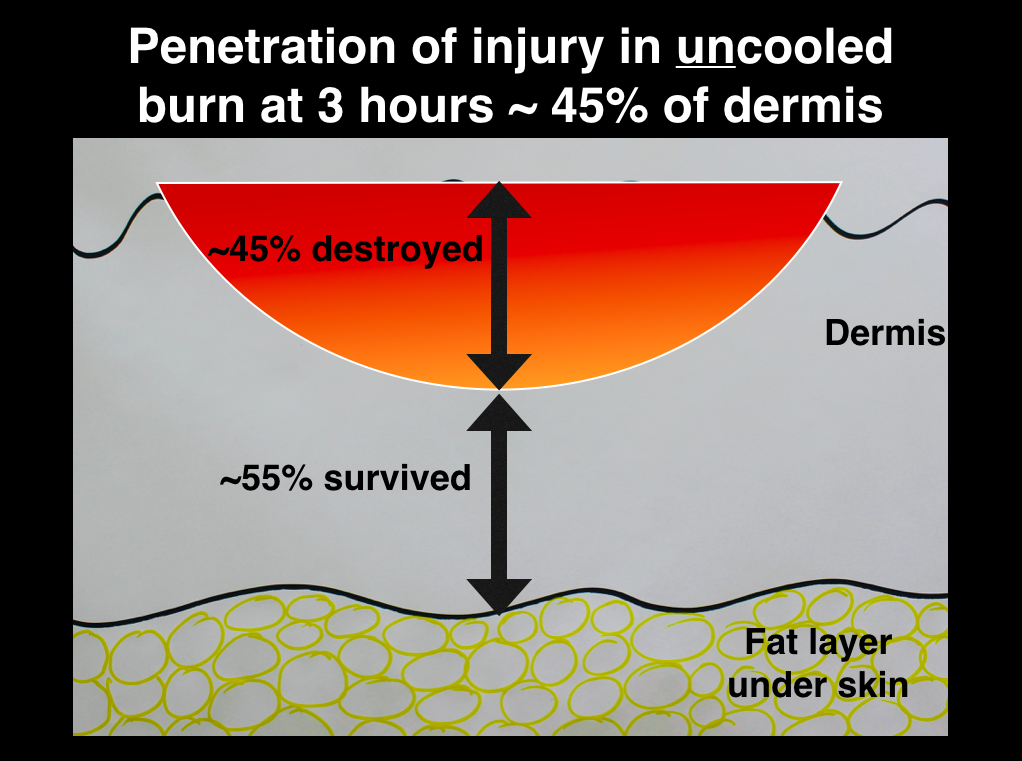

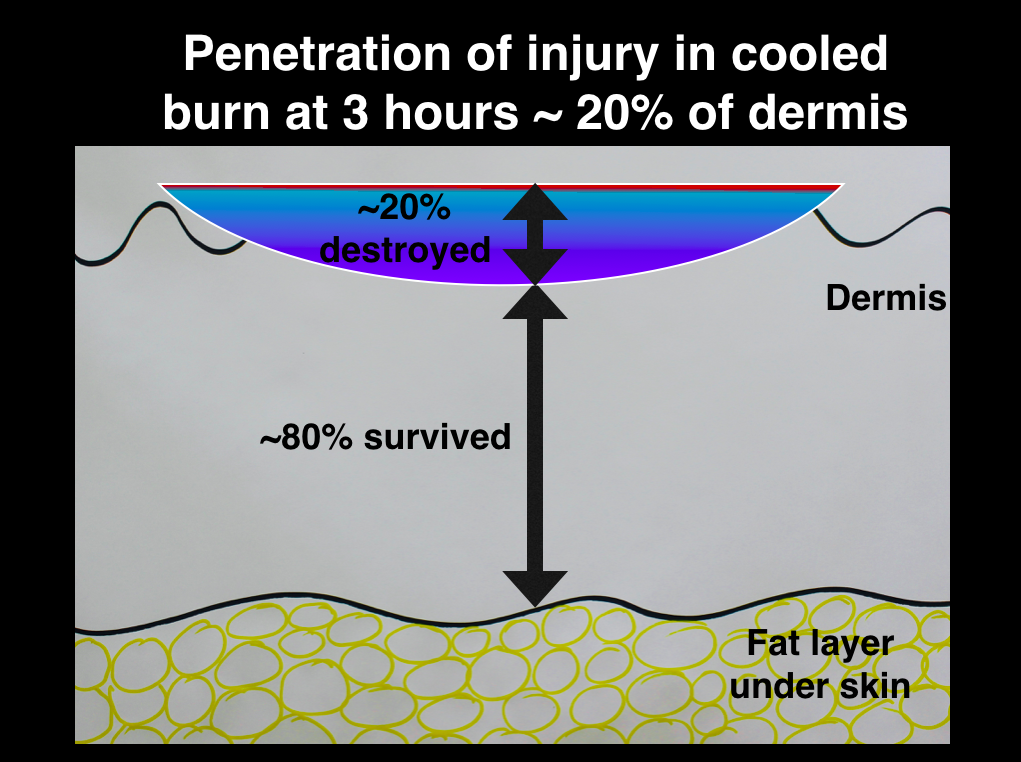

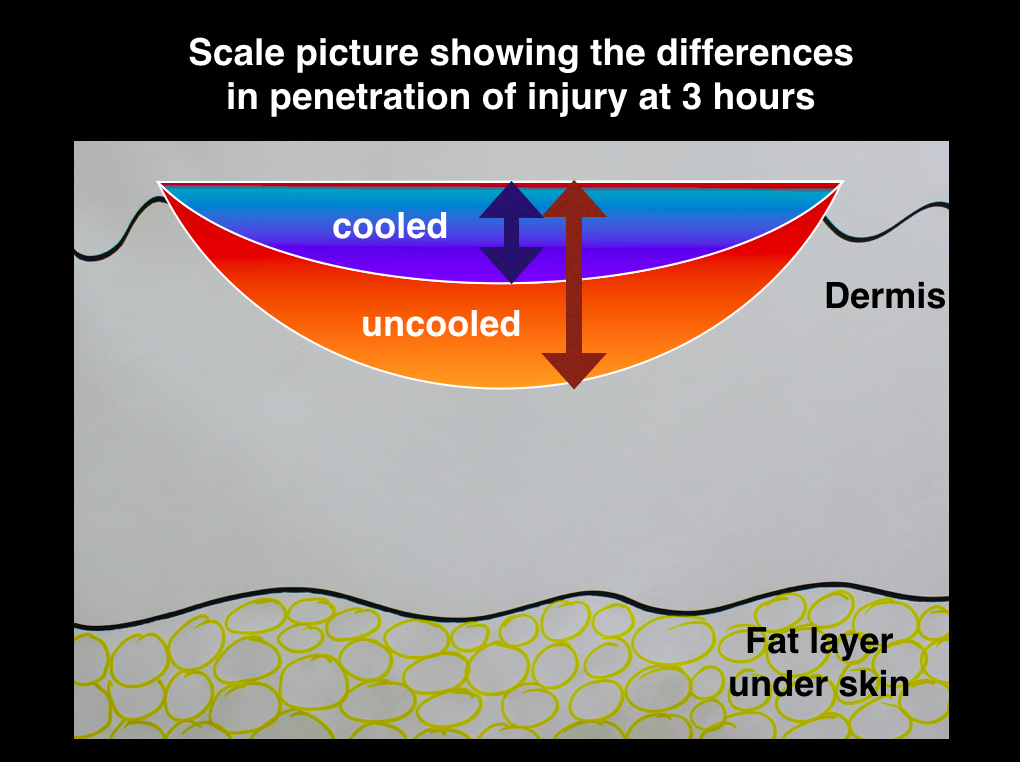

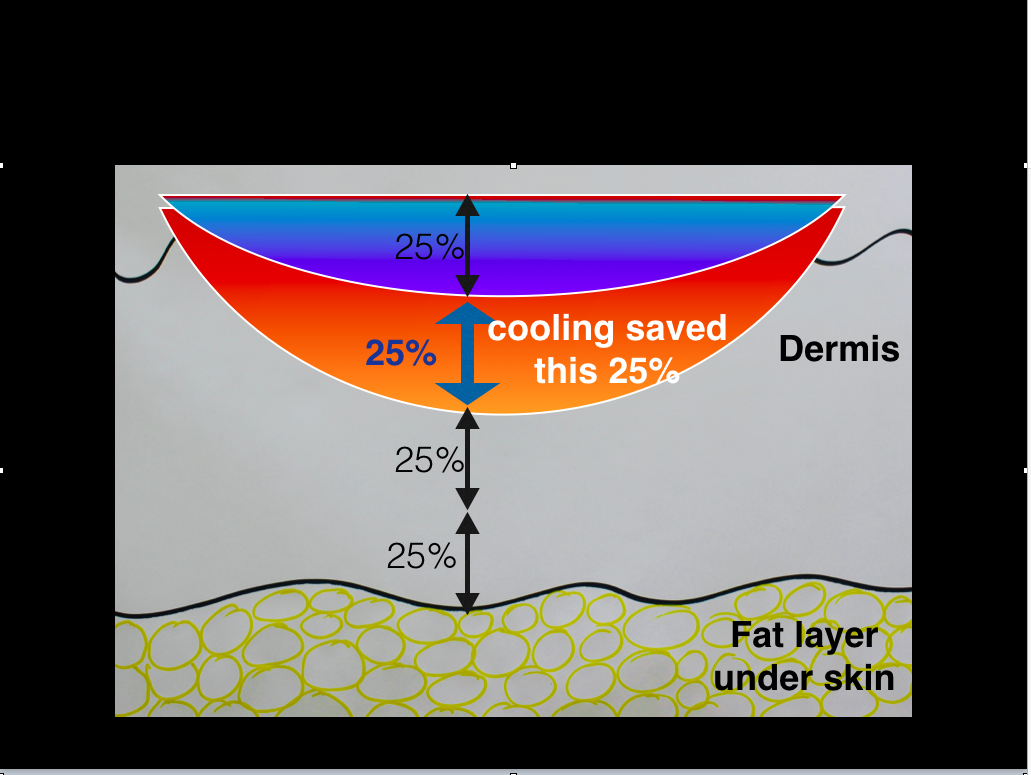

Our results showed that for every individual the cooled burns were less damaged than the uncooled burns. When we put all our results together, in the uncooled burns the damage had penetrated to an average depth of 44.9% of the total thickness of the dermis. The corresponding penetration of damage in the cooled burns was 19.7% (p<0.0001). A average of 25.2% less depth of penetration of injury into the dermis.

Uncooled burn

Uncooled burn

Cooled burn

Cooled burn

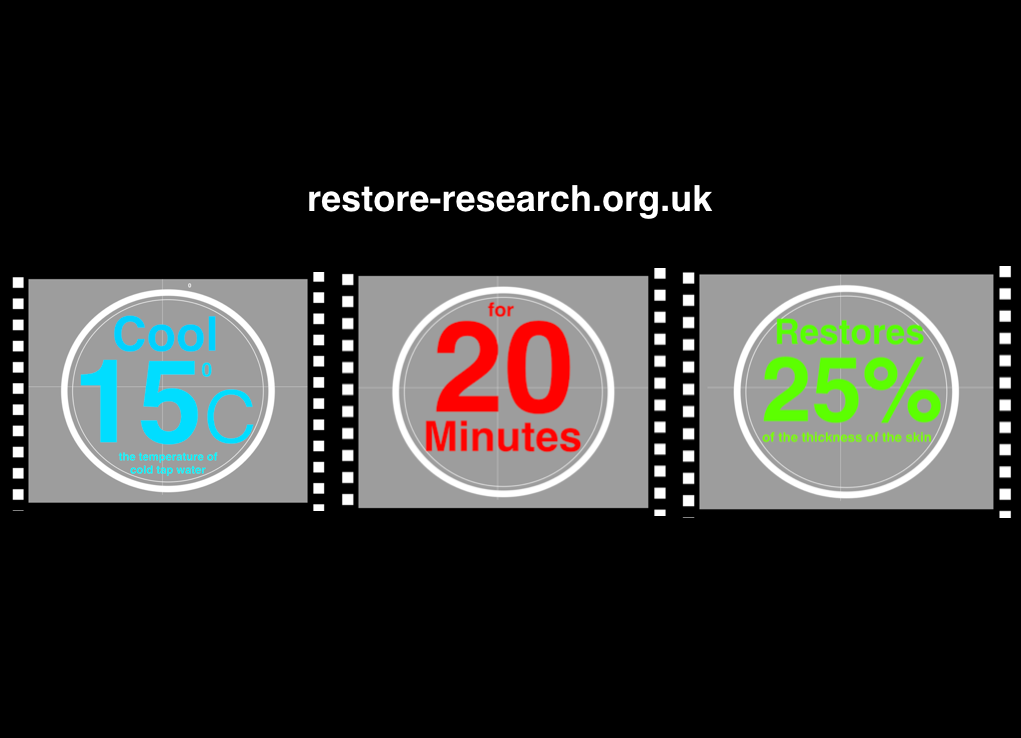

Our conclusion is that for similar injuries, such as a scald, cooling with cold tap water (~150C or 600F) for 20 minutes can reduce the amout of penetrating damage to the skin by 25%. If the burn is at that critical point between healing without a scar and healing with one, then the first aid will make a crucial difference to the rest of the patient's life.

The benefit of cooling

This research has been published in the British Journal of Surgery in October 2019

A human burn model that quantifies the benefit of cooling as a first aid measure.

Mr E.H. Wright, Mr M. Tyler, Prof B. Vojnovic, Mr J. Pleat, Prof A. Harris, Prof D. Furniss

BJS 2019; 106: 1472-1479

The authors thank the patients for their generosity and spirit in consenting to be involved in this study. We thank Restore-research (Hugh Wright was the Duke of Kent Clinical Research Fellow) and the Royal College of Surgeons for funding this.

Restore-research is a charity which carries out research into burns and wound healing. Visit our website www.restore-research.org.uk and find out more about us. Without donations we cannot do any research, so if you think this sends a useful message then a donation, no matter how small, would be gratefully received. Our website explains how you can donate.

I hope you found this story interesting and that it makes a difference, someday to someone.

Thank you

Story by Michael Tyler